How does rescoring with machine learning work?

Mascot Server ships with Percolator, which is a well-known algorithm that uses semi-supervised machine learning to improve the discrimination between correct and incorrect spectrum identifications. This is often termed rescoring or refining with machine learning. What exactly does it mean, and how does it work?

Separating correct from incorrect matches

When you submit a search against a protein sequence database, the results are always a mixture of correct and incorrect peptide matches. For example, maybe the correct sequence isn’t in the database, or the spectrum has tall noise peaks that happen to match and score better against the wrong sequence.

The Mascot ions score is designed so that the correct matches should mostly have high score and incorrect matches should mostly have low score. You can then set a score threshold that throws away most of the incorrect matches and keeps most of the correct ones.

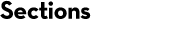

Unfortunately, real-life data sets hardly ever have a neat division between correct and incorrect matches when plotted in the single scoring dimension.

The above schematic illustrates a particularly bad case, where most of the correct matches have a score in the same range as the incorrect matches. No matter where you set the score threshold, you either lose a lot of correct matches or you let in a lot of incorrect matches.

Multiple feature dimensions

Refining results with machine learning means using more than one dimension to separate the populations. This works because incorrect matches often differ systematically from correct matches.

You can enable refining with machine learning either in the search form when submitting the search, or in format controls in the summary report. When it’s enabled, the first thing that Mascot does at the end of the database search is calculate a range of features for each peptide match. These are saved as a Percolator input (pip) file. One of the features is simply the Mascot ions score. Another example is precursor mass error. Mass error of incorrect matches tends to be randomly distributed, while mass error of correct matches tends to be clustered around zero. Other features include charge state, number of missed cleavages, proportion of matched fragment ion intensity and so on.

Purpose of target-decoy searching

In order to make use of this, semi-supervised machine learning, like Percolator, needs labelled examples of correct and incorrect peptide identifications. Because the search engine score is insufficient in separating the two populations, the search engine cannot automatically label matches in the target database. (If we were able to do that, we would not need machine learning!)

The solution is automatic target-decoy searching. Mascot runs a search against the target sequence database, and simultaneously a search against reversed or randomized sequences – the decoy proteins. Anything that matches in the decoy database is incorrect by definition. As long as the decoy peptides are statistically similar to target peptides (similar length and mass distributions), the decoy matches can be assumed to model the incorrect matches in the target database.

The decoy matches provide the ‘negative’ examples for semi-supervised machine learning, and the target database is an unknown mixture of negatives and positives. Percolator initially chooses high-scoring target matches as the ‘positive’ examples. Then, it iteratively trains the model until it finds an optimal separation in the multidimensional space.

Multidimensional separation

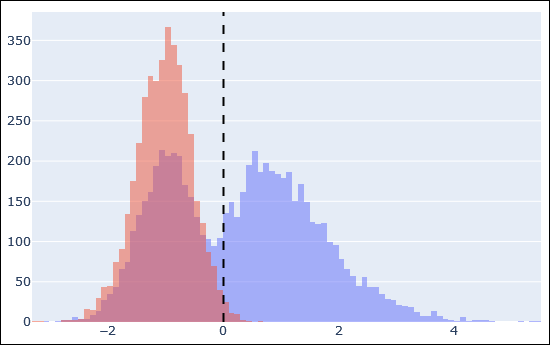

After finding the optimal separation in the multidimensional feature space, Percolator calculates a q-value and posterior error probability (PEP) for each peptide match, which are well explained in Posterior Error Probabilities and False Discovery Rates: Two Sides of the Same Coin. Mascot reads back the PEP values and finds a PEP threshold that yields the target FDR. This provides a new score threshold that condenses the multidimensionality into a single number.

The above histogram is an example of target peptide matches in blue and decoy matches in red after Percolator rescoring. The dashed line is the 1% FDR threshold. There is a very clear separation between incorrect target matches (blue superimposed on red, left side of the dashed line) and correct target matches (blue, right side).

Normally, the high-scoring matches in the target database before and after rescoring are pretty much the same. What usually improves is the status of matches with a middling Mascot score. Any match whose calculated features are similar to the high-quality ‘positive’ examples are boosted, because they cluster together in the multidimensional space. This is how machine learning is making use of the additional information.

Enable by default?

Enabling rescoring often increases the number of peptide identifications. Why is it not enabled by default?

You can make Percolator the default by setting the mascot.dat option:

Percolator 1

The factory default is 0 (not enabled). You can also set the default for the search form as a cookie.

It’s very important to be able to turn off machine learning if it isn’t working correctly with your data. For example, the Percolator model can fail to converge if you have too few target matches, or too few decoy matches, or the matches aren’t of sufficient quality. When the model does converge, Percolator rarely makes the results worse, but it’s important to be able to compare them with and without machine learning to appreciate whether and how much of a difference it makes. Always study the machine learning quality report.

What machine learning cannot do

Machine learning is not a substitute for a proper statistical scoring scheme. Remember the old adage garbage in, garbage out. Something (that is, the Mascot ions score) must provide good enough discrimination for semi-supervised machine learning to get started. It cannot magically turn poor quality PSMs into high-quality PSMs. The better the database search results, the better the machine learning.

Rescoring also cannot be used for discovering peptides that are not in the database, because it doesn’t ‘invent’ new peptides during the training step. It just uses peptide identifications provided by the search engine. It’s as important as ever to make sure your search space is complete: the right sequence database(s); suitable fixed and variable modifications; enzyme and missed cleavages.